MCL Injury:The Basics

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is one of four major ligaments of the knee. The other ligaments are the lateral collateral ligament (LCL), anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL).

The MCL is a band of tissue that starts on the inside of the femur (thigh bone), and crosses the knee before it attaches to the inside of the tibia (shin bone). It provides stability to the inside of the knee.

The primary function of the MCL is to resist valgus forces applied to the knee. This means it prevents the knee from being forced inward.

There are two separate components to the MCL. The superficial MCL is the component that is closer to the skin. This structure is more important for resisting the inward forces applied to the knee. The superficial MCL is more commonly injured. The deep MCL is deeper under the skin. It helps stabilize rotation of the knee. The deep MCL is closely associated with medial meniscus.

How does MCL injury happen?

MCL injuries are common. The MCL is injured in almost half of knee injuries involving the ligaments. It is especially common in skiing, football, and hockey.

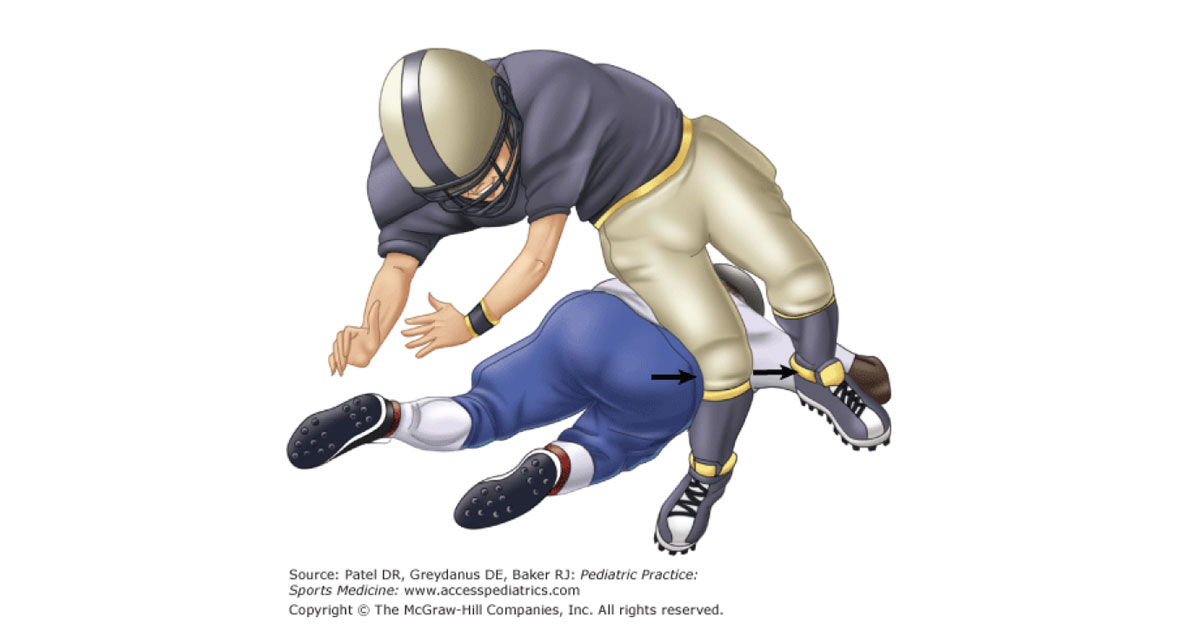

Injury occurs after a force is applied to the outside of the knee, forcing it inwards. Outward rotation of the foot at the moment of injury can also contribute to injuring the MCL. This can be a contact injury where a direct blow forces the knee inwards, or a non-contact injury. Males and females are at equal risk for MCL injury.

MCL injury can also occur in conjunction with other knee ligament injuries such as the ACL. It can also occur in conjunction with injuries to the shock absorbers of the knee called the meniscus.

— Read more about ACL injury here —

An MCL injury can feel different depending on the severity.

A popping sound is often heard or felt at the time of injury. Patients typically experience pain and swelling. The pain is often localized to the inner part of the knee. For more severe injuries, patients may experience a sensation of their knee giving way as they try to weight it.

How is MCL injury diagnosed?

MCL tears are typically diagnosed by asking the patient what happened when the injury occurred and conducting a physical exam. There may be bruising or pain on the inside of the knee. Damage to the MCL can be felt on physical exam by the examiner by stressing the MCL. The other 3 major ligaments of the knee are routinely tested on physical exam as well.

An MRI scan can aid in the diagnosis and characterize the severity of the tear, as well as assess for any other soft tissue injures of the knee, however, they are often not necessary.

How is MCL injury treated?

MCL injures generally have excellent outcomes, particularly when they occur in isolation without another ligament injury.

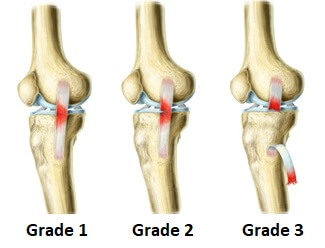

Treatment depends on severity, which is evaluated by a grading system.

MCL Injury Grade

Grade I (mild) injuries are a stretching type of injury. In this circumstance, very few MCL fibers are actually torn, and there is unlikely to be any instability felt.

Grade II (moderate) injuries are incomplete or partial MCL tears. When physically examining the knee, the knee will still have support from the MCL, but may feel slightly unstable.

Grade III (severe) injuries are complete MCL tears. The knee will have no “end point” when the MCL is stressed by the examiner during a physical exam, which means that the knee will feel like it could easily move sideways.

Treatment of Grade I and II MCL injuries

Management of Grade I and II injuries is focused on pain control and reducing swelling. This can be accomplished with rest, ice, and anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen. Early rehab is focused on restoring range of motion of the knee, and regaining quadriceps function. A hinged knee brace is helpful for protecting the knee during the rehabilitation process. Patients can weight bear as soon as the pain is tolerable. Patients with Grade I injuries can typically return to sport and activity in 1 to 2 weeks, while patients with Grade II injuries can return by 3- 4 weeks.

Treatment of Grade III MCL injuries

Isolated Grade III injuries, where the MCL is the only ligament torn, are rare. When they do occur, they can be treated without surgery. The initial treatment is similar to Grade I and II tears, and focuses on pain management, bracing, and rest. The patient can return to sport and activity as early as 5-7 weeks, depending on the sport and player position.

However, some Grade III injuries will require surgery. After a course of nonoperative management, if there is persistent laxity (looseness) to the knee, surgery can be considered. Additionally, if there is a Grade III injury due to a piece of bone pulling off, rather than the ligament itself rupturing, surgery is often recommended. Surgery may also be recommended if other ligaments such as the ACL, or the meniscus, are torn.

MCL surgery can either involve repairing the existing MCL or reconstructing it using tissue from elsewhere. This tissue may be autograft, meaning it comes from elsewhere on the patients’ body e.g. hamstrings or Achilles tendons, or it may be allograft, meaning it comes from a tissue donor. If surgery is required, your surgeon will discuss the specific options with you.

— WATCH a short video about MCL injury and reconstructive surgery —

Expert Contributor

Matthew Getzlaf, Orthopaedic Surgery Resident PGY 4, University of Saskatchewan

References

Hassebrock J, Guldbrandsen M, Asprey W, Makovicka J, Chhabra A. Knee ligament anatomy and biomechanics. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2020: 28(3) 80-86

Kim C, Chasse P, Taylor D. Return to play after medial collateral ligament injury. Clin Sports Med. 2016; 35: 679-696

Miyamoto R, Bosco J, Sherman H. Treatment of medial collateral ligament injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2009;17: 152-161

Moran J, Katz L, Schneble C, Li D, Kahan J, Wang A, Porrino J, Jokl P, Hewett T, Medvecky M. Injury to the meniscofemoral portion of the deep MCL is associated with medial femoral condyle bone marrow edema in ACL ruptures. JBJS. 2021; 21:1-7

Wijdicks CA, Griffith CJ, Johansen S, Engebretsen L, LaPrade RF. Injuries to the medial collateral ligament and associated medial structures of the knee. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-American Volume. 2010;92(5):1266–80.