Overuse or underuse injury?

You’ve probably had, or know someone who’s had, an injury called an ‘’overuse’’ injury.

Maybe it happened after doing seemingly not much, or after having already stopped activities.

You may be overly excited at the beginning of the ski season, go for 2 consecutive full days (perhaps you also want to make your $150 daily ticket profitable) and then oops… your knee starts to hurt. Even worse, as the fatigue creeps up at the end of the day, your knee collapses into valgus and your ACL gives up!

I actually had the idea to write this article after working with a hockey player with recurrent groin strain. Every time he was seeing his therapist, his main advice was to ice and rest because his groin was an ‘’overuse’’ injury. Then guess what? He was coming back without the appropriate level of preparation and injuring himself again. In that case, I called it an ‘’underuse’’ injury and then it all made sense to him.

Training load and the dose-response

Injuries can be devastating and life changing, but wait a minute! Can training hard and consistently with the appropriate recovery actually help to make your body more bulletproof?

Lots of research has been done over the last decade showing that workload or physical stress can have a positive effect or negative effect on injury risk and sickness.1

Indeed, resting on your couch often isn’t always the best solution, neither is running a marathon to get in shape.

When dosing the appropriate training with enough recovery, your body will adapt by improving it’s aerobic fitness, anaerobic capacity, strength, neuromuscular control and tissue resiliency. Even your tendons will adapt and thicken to some types of load by increasing collagen synthesis.2

Training load, or workload, is traditionally a measure of both external and internal load.

- External load (i.e. the physical work) can be measured by distance, power output, speed, GPS tracking, weight lifted or duration.

- External load (i.e. the physical work) can be measured by distance, power output, speed, GPS tracking, weight lifted or duration.

Sport scientists often calculate an arbitrary number based on these 2 types of loads to track their athlete’s workload overtime and make recommendations to the coaching staff.

The “magic” ratio

Sport Scientists will often use the Acute : Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR) to compare the acute training load, usually the last 5 to 10 days, to the chronic training load, usually the last 4 to 6 weeks.

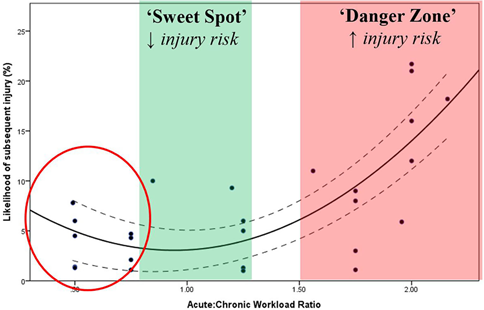

When they are both relatively even, between 0.8 and 1.3, the risk of injury is relatively low (see the green ‘Sweet Spot’ on the graph below).

More injuries and illness tend to occur when there are spikes in the acute training load (see the red ‘Danger Zone’ below).

You can also observe on this graph an exponential rise of injuries when the ACWR is above 1.5 and a similar effect following periods of undertraining when the ACWR is below 0.8.

A significant number of studies also demonstrate that maintaining a high chronic workload may decrease the likelihood of injuries.3-5

In other words, training hard and consistently usually creates positive physical and physiological adaptations and inconsistency in your training or sport routine may have adverse effects.

However, you may ask yourself how much is enough?

A simple way to answer that is to analyze your sport and figure out the intensity, duration of the efforts and movements that have to be performed at play or during competition. Once you know this information, you can train to sustain those efforts and improve those attributes to improve your resiliency and performance.

Is injury prevention all about training load monitoring?

When I was working with the Canadian Sport Institute and Swimming Canada, there was lots of work done to monitor the athlete’s training load. Having an athlete out of training for a few weeks significantly decreases their chance to improve their performance during the given season.

Bad news… It wasn’t always working and they were still in need of my services.

Injuries are multifactorial and they can also be influenced positively or negatively by biomechanical factors, emotional stressors and lifestyle choices. For example, high academic and emotional stress6-7 or anxiety8 increase injury risk. Similarly, athletes who sleep less than 8 hours per night have a 1.7x greater risk of injury compared to those who sleep more than 8 hours9. Interesting!

I hope this article brought you a new perspective on how to be proactive about your health and below are a few key things I think you can take out from it.

Key messages

- Maintaining a high chronic load with the appropriate recovery can help to decrease injury risk.

- Train to meet the demand of your sport. A bodybuilding program won’t help you much for skiing, rock climbing or playing soccer!

- Gradual overload is key. When coming back from a break, injury or sickness, gradually increase your training load to prevent an ‘’undertraining’’ injury.

- You can use a training load monitoring app, smart watch or simply a calendar to track your physical activities. This will help to see the big picture and avoid significant spikes of training.

Contributing Expert

Didié Hamel-Jolette is an Athletic Therapist, Strength Coach and Concussion Rehab Specialist at Keystone Health in Revelstoke, BC. He has helped numerous national team athletes in swimming, bobsleigh, judo, trampoline and taekwondo and also a bunch of active individuals from various sport backgrounds. He recently moved to Revelstoke to follow his passions.

References

- Pitre C. Bourdon, Marco Cardinale, Andrew Murray, Paul Gastin, Michael Kellmann, Matthew C. Varley, Tim J. Gabbett, Aaron J. Coutts, Darren J. Burgess, Warren Gregson, and N. Timothy Cable. Monitoring Athlete Training Loads: Consensus Statement. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2017, 12, S2-161-S2-170

- Alfons Mascaró, Miquel Àngel Cos, Antoni Morral, Andreu Roig, Craig Purdam, Jill Cook. Load management in tendinopathy: Clinical progression for Achilles and patellar tendinopathy. Apunts Med Esport. 2018;53(197):19-27

- Hulin BT, Gabbett TJ, Lawson DW, Caputi P, Sampson JA. The acute:chronic workload ratio predicts injury: high chronic workload may decrease injury risk in elite rugby league players. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(4):231–236. PubMed doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094817

- Gabbett TJ, Hulin BT, Blanch P, Whiteley R. High training work- loads alone do not cause sports injuries: how you get there is the real issue. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(8):444–445. PubMed doi:10.1136/ bjsports-2015-095567

- Soligard T, Schwellnus M, Alonso J, et al. How much is too much? (part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on training and competition loads and the risk of injury. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(17):1030–1041. PubMed doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096581

- Ivarsson A, Johnson U, Andersen MB, et al. Psychosocial factors and sport injuries: meta- analyses for prediction and prevention. Sports Med 2017;47:353–65.

- Mann JB, Bryant KR, Johnstone B, et al. Effect of physical and academic stress on illness and injury in division 1 college football players. J Strength Cond Res 2016;30:20–5.

- Li H, Moreland JJ, Peek-Asa C, et al. Preseason anxiety and depressive symptoms and prospective injury risk in collegiate athletes. Am J Sports Med 2017;45:2148–55.

- Milewski MD, Skaggs DL, Bishop GA, et al. Chronic lack of sleep is associated with increased sports injuries in adolescent athletes. J Pediatr Orthop 2014;34:129–33.