Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injury: the basics

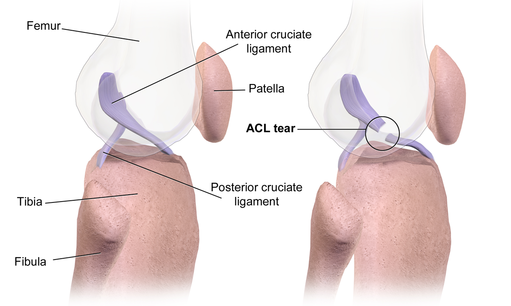

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of four stabilizing ligaments in the knee. Its role is to prevent the tibia (shin bone) from moving too far forward, as well as to prevent hyperextension of the knee (when the knee extends past its normal range of motion).

An intact ACL also protects the menisci (the cartilage that provides cushioning between the thigh and shin bones) during athletic maneuvers, such as landing, pivoting and decelerating from a run.

The ACL is one of the most frequently injured ligaments of the knee, with approximately 250,000 people in the U.S. alone suffering an ACL injury each year.1

It is also commonly injured in pivoting sports such as skiing, soccer and basketball, or in contact sports such as football or rugby.

ACL injury frequently affects young, active people, with females being at greater risk than males. 2-7

There are several theories put forth to explain this gender phenomenon. Overall the research suggests that female athletes put greater stress on their knees due to differing biomechanics (the way the body moves) compared to males.

For example, females have a wider pelvis resulting in a higher incidence of genu valgus (knock knees) which can increase the risk of abnormal biomechanics when landing from a jump. Females also tend to land jumps with less knee flexion and also have more hypermobile joints, both of which can increase the risk of ACL tears.

Regardless of age or gender, an ACL injury can be devastating.

Short term impacts can include pain, loss of mobility and function, withdrawal from sport, and psychological conditions such as anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress.

The long-term impacts can include an increased risk of obesity, osteoarthritis and re-injury. 8-10

How does ACL injury occur?

At least 70% of ACL injuries occur as non-contact (without a direct blow to the knee).11-13

A common body position associated with non-contact ACL injury is shown in Figure 1.

Injury commonly involves:14-16

- internal rotation of the hip;

- the knee being close to full extension;

- the foot is planted; and the body is decelerating, leading to inward collapse of the knee.

ACL injury risk factors

Scientific data from several fields show that numerous factors affect a person’s risk of ACL injury.

Some of these factors have been reviewed by LaBella and colleagues7 and include:

- prior injury

- younger age and gender, with females having a higher rate of injury immediately after a growth spurt

- greater weight and Body Mass Index (BMI)

- lack of muscle strength and coordination

Diagnosis of an ACL injury

Diagnosis of an ACL injury will be most accurate after any swelling has decreased. After this a practitioner should be able to diagnose an ACL injury based on a patient’s history and physical exam.

When to see a Doctor

The signs and symptoms of an ACL injury are not always the same. It’s important to see a doctor if you experience any of the following:

- Knee pain or swelling that last more than 48 hrs

- Difficulty standing or walking on the injured knee

- Inability to support your weight on the injured knee

- A deformed or odd appearance of the injured knee compared to the uninjured one

Several indications of an ACL injury are:

- A history of an acute twisting or pivoting injury, usually with immediate pain and rapid swelling

- Hearing or feeling an audible ‘pop’ at the time of injury

- Episodes of ‘giving way’ or feelings of knee ‘going out’

- Physical assessment showing looseness in the knee with back to front and rotational testing

If the extent of an ACL tear is unclear, or to determine the amount of damage to other structures (i.e. meniscus, other ligaments), or to confirm a diagnosis, imaging such as an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) may be used, but is not usually necessary for a diagnosis.

ACL treatment options

Although a torn ACL can occasionally heal on its own, this is unusual. Some people with a deficient ACL do well with conservative treatment, however, the most effective treatment in terms of restoring knee function is surgery.

Regardless of treatment option, the aim overall is to:

- Restore knee function

- Prevent further injury

- Optimize long-term quality of life

Non-surgical treatment

Not having surgery to treat an ACL injury may be appropriate for patients who aren’t involved in any type of sport activity, those with sedentary jobs that involve sitting at a desk, or those that don’t participate in any type of recreational activities that require pivoting stability.

Non-operative treatment could involve the following:

- Structured Rehabilitation – some patients can cope with a torn ACL following an intensive and structured rehabilitation program. We will discuss ACL rehabilitation in future articles.

- Knee brace – some people with a torn ACL can be stable in a custom fitted functional brace for sport and work.

- Lifestyle modifications – some people with a torn ACL will decrease the intensity of their activities, or stop all pivoting and contact sports.

ACL repair

Repair of the ACL using sutures was first described in the early 1900s. It involves stitching the injured / torn ligament(s) back onto the femur.

ACL repair was the most common treatment for ACL injury in the 1970s and 1980s. However, due to multiple research studies reporting poor long-term outcomes, with failure rates anywhere from 40% to 100%, it fell out of favor as the surgical treatment of choice (reviewed in17).

In recent years, due to complications associated with ACL reconstruction, and with advancements in surgical technique and imaging, ACL repair is once again receiving attention as a potential treatment for specific types of ACL tears.18-22

However, ACL repair is currently not the standard of care in North America, and more research is required to determine its exact role in the treatment of ACL tears.

ACL reconstruction

ACL reconstruction is currently the gold standard of care for ACL injuries, particularly for young, active individuals and athletes who plan to return to a high level of sporting activities.

In ACL reconstruction, the torn ACL tissue is surgically removed and replaced with a tendon taken from around the knee, such as 1 or 2 hamstring tendons or a portion of the patellar or quadriceps tendon (autograft). Another options, usually reserved for patients 40 years or older, is an allograft tendon.

Allograft – tendon originating from another person, typically a cadaver.

Autograft – tendon taken from another location in the patient’s body.

Activities you can do in addition to prehab and rehab exercises

Winter Activities

English Subtitles

French Subtitles

Tagalog Subtitles

Summer Activities

— More exercises and activities can be found here —

References

1. Griffin LY, Albohm MJ, Arendt EA, et al. Understanding and preventing noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: a review of the Hunt Valley II meeting, January 2005. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(9):1512-1532.

2. Arendt E, Dick R. Knee injury patterns among men and women in collegiate basketball and soccer. NCAA data and review of literature. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(6):694-701.

3. Myklebust G, Maehlum S, Holm I, Bahr R. A prospective cohort study of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in elite Norwegian team handball. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1998;8(3):149-153.

4. Stevenson H, Webster J, Johnson R, Beynnon B. Gender differences in knee injury epidemiology among competitive alpine ski racers. Iowa Orthop J. 1998;18:64-66.

5. Caine D, Caine C, Maffulli N. Incidence and distribution of pediatric sport-related injuries. Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16(6):500-513.

6. Dingel A, Aoyama J, Ganley T, Shea K. Pediatric ACL Tears: Natural History. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39(Issue 6, Supplement 1 Suppl 1):S47-S49.

7. LaBella CR, Hennrikus W, Hewett TE. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):e1437.

8. Tengman E, Brax Olofsson L, Nilsson KG, Tegner Y, Lundgren L, Hager CK. Anterior cruciate ligament injury after more than 20 years: I. Physical activity level and knee function. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(6):e491-500.

9. Whittaker JL, McKay CD, Batt ME. Prevention, management and long-term consequences of sport and exercise-related musculoskeletal disorders. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2019;33(1):1-2.

10. Wright RW, Dunn WR, Amendola A, et al. Risk of Tearing the Intact Anterior Cruciate Ligament in the Contralateral Knee and Rupturing the Anterior Cruciate Ligament Graft during the First 2 Years after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Prospective MOON Cohort Study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2007;35(7):1131-1134.

11. Boden BP, Dean GS, Feagin JA, Jr., Garrett WE, Jr. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Orthopedics. 2000;23(6):573-578.

12. McNair PJ, Marshall RN, Matheson JA. Important features associated with acute anterior cruciate ligament injury. N Z Med J. 1990;103(901):537-539.

13. Levine JW, Kiapour AM, Quatman CE, et al. Clinically relevant injury patterns after an anterior cruciate ligament injury provide insight into injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(2):385-395.

14. Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: Part 1, mechanisms and risk factors. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(2):299-311.

15. Hewett TE, Torg JS, Boden BP. Video analysis of trunk and knee motion during non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes: lateral trunk and knee abduction motion are combined components of the injury mechanism. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(6):417-422.

16. Boden BP, Torg JS, Knowles SB, Hewett TE. Video analysis of anterior cruciate ligament injury: abnormalities in hip and ankle kinematics. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(2):252-259.

17. van der List JP, DiFelice GS. Primary repair of the anterior cruciate ligament: A paradigm shift. The Surgeon. 2017;15(3):161-168.

18. DiFelice GS, Villegas C, Taylor S. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Preservation: Early Results of a Novel Arthroscopic Technique for Suture Anchor Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2015;31(11):2162-2171.

19. Achtnich A, Herbst E, Forkel P, et al. Acute Proximal Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears: Outcomes After Arthroscopic Suture Anchor Repair Versus Anatomic Single-Bundle Reconstruction. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2016;32(12):2562-2569.

20. van der List JP, DiFelice GS. Arthroscopic Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair With Suture Augmentation. Arthroscopy techniques. 2017;6(5):e1529-e1534.

21. Liao WL, Zhang Q. Is Primary Arthroscopic Repair Using the Pulley Technique an Effective Treatment for Partial Proximal ACL Tears? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2020.

22. DiFelice GS, van der List JP. Clinical Outcomes of Arthroscopic Primary Repair of Proximal Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears Are Maintained at Mid-term Follow-up. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2018;34(4):1085-1093.