Rehabilitation & Treatment of Tendinopathy

Tendinopathy, or inflammation of the tendon, is a common condition that can affect many areas of the body.

It is commonly seen in the elbow, shoulder, knee, and ankle, but can be present in any tendons. It is commonly caused by overuse and repetitive strain, but can also be caused by sudden trauma or some underlying medical conditions.

Risk of developing tendinopathies increases with age and is most seen in people over the age of 35 [1]. Repetitive overuse in activities such as running, throwing athletes, and manual labour, also increase the risk of developing tendinopathies.

The basics

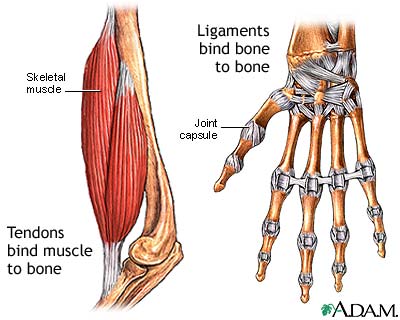

Tendons are the tissues that connects muscles to bones.

They consist of a tough band of tissue that allows the force generated by muscles to transmit into bones resulting in movement.

Normally this tissue is made of densely packed collagen fibres.

When the tendon becomes damaged from repetitive use, these fibres become disorganized, the tendon thickens and is infiltrated with new blood vessels [2].

This altered structure leads to impairment and associated pain. In areas where the tendons pass through narrows spaces (i.e the shoulder) the thickening of the tendon and associated bursa can lead to impingement and further dysfunction.

Tendonitis symptoms

Symptoms will vary based on where the tendon is located.

In general, however, symptoms may include:

- Pain with active range of motion of the joint of concern. Often pain occurs after completion of activity.

- Tenderness over the insertion of the tendon. For example, the boney bumps at the sides of the elbow, near the kneecap, top of the shin, or at the back of the heel.

- Many tendinopathies have delayed pain called “latency”. What this means is that often movements are initially only mildly painful. This pain subsides, but then later (ie several hours to a day later), more severe pain develops.

- Tendinopathy may also cause referred pain, muscle spasm, tenderness, or joint stiffness. [3]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be made based on the history of the injury and physical exam of the affected areas.

Ultrasound imaging is not required to diagnose tendonitis, but it can be used to determine the extent of injury to the tendon, or if there is some uncertainty in the diagnosis after a thorough history and physical exam.

Treatment options for tendonitis

The main goals of treatment are to restore movement of the affected joint without pain and to maintain strength of the surrounding muscles while providing enough time for the tendon to heal.

Activity modification and tendon load – Activity modification requires limiting the volume and intensity of activity using the injured tendon for a period of time, to allow for symptoms to improve.

Biomechanical modification – The goal of this treatment is to modify any underlying biomechanical issues that may contribute to the development of tendinopathy. This would include ergonomics at work or home, walking and running mechanics or sport-specific movement mechanics modifications. These studies should be undertaken with a trained practitioner (such as a physiotherapist, occupational therapist or kinesiologist).

Heavy-load resistance training – The primary rehabilitation method with the strongest evidence is progressive resistance training using relatively heavy loads.

There are several types of resistance exercise. Eccentric exercise occurs when the muscle is loaded while it is lengthening (i.e. slowly lowering the weight during a bicep curl or the downward movement during a squat); concentric exercise is load while the muscle is shortening (i.e. lifting weight in a bicep or standing up during a squat); isometric exercise is the maintenance of muscle force when a muscle held at a constant length (i.e. plank exercises, wall sits).

Most evidence comes from exercises that emphasize eccentric movement or a combination of eccentric and concentric movement. There is no evidence showing one type of movement has better outcomes than the other.

Anti-inflammatory medications – Most tendinopathies do not demonstrate significant inflammation in the tendon. However, in the early stages, there may be small amounts of inflammation that contribute to pain. In the longer term, anti-inflammatories may impair healing and remodeling of the tendon. Short courses of anti-inflammatories can be helpful for early injury or painful flares, but should be avoided for long term management.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) — Oral NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen, etc) and acetaminophen may be helpful for short-term (eg, five to seven days) pain relief. Topic anti-inflammatories (e.g. Voltaren, Mulitprofen) have been shown to be effective for short-term pain control [4-7] and may have less side effects than oral medications.

Glucocorticoids (Steroid injections) – Evidence for the effectiveness and risk of steroid treatment varies by the route of delivery (injection versus oral) and the site of injury. In chronic patellar, Achilles tendon, and elbow tendinopathies, injections have not been shown to be helpful and may increase the risk of further damage [8,9]. In acute injury at these sites, local glucocorticoid therapy may be useful for treating symptoms. In chronic rotator cuff tendinopathy, injections may have some benefit, but the evidence is not strong [10].

Topical nitroglycerin (glyceryl trinitrate) – Nitroglycerin patches can be placed are placed directly over affected tendons to deliver nitric oxide, which may stimulates collagen synthesis in tendon cells, among its many effects.

The evidence for this treatment is mixed, with most studies showing no benefit. However, it may be considered in refractory cases in combination with other rehabilitation strategies as it is relatively low cost and safe.

These medications should be used by people who have low blood pressure, migraine headaches, rosacea or those taking other medications that contain nitrates. You should discuss these medications with your doctor.

Shock wave therapy – The evidence for extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) in the treatment of tendonitis is mixed with some studies showing benefit while others show no benefit. Most reviews (which combine studies together) conclude there is limited-to-no benefit versus placebo. However, in cases of chronic tendonitis it can be considered as an adjunct to other physical rehabilitation techniques above.

Other treatments with limited evidence or ongoing research

Ice or heat – These may provide relief of symptoms, but have limited evidence in their effectiveness as a treatment. They are inexpensive and safe if use appropriately and may be used in conjunction with other modalities.

Stretching – Despite no definitive studies, many medical professionals routinely include stretching in their programs for the prevention and treatment of tendinopathies. If prescribed, stretching should be performed following activity when muscles are warm. Stretching should be performed on a regular basis (3-5 times per week) for sustained improvement in flexibility.

Prolotherapy – Prolotherapy involves the injection of a substance, usually dextrose (sugar) and anesthetic into the tendon to stimulate a healing response. There are no large, randomized studies supporting it’s use, but some small trials show modest benefit. [11-12].

Sclerotherapy – As discussed above, tendinopathy results in new blood vessel formation in tendons. Sclerotherapy uses a substance injected into the tendon to reduce these new blood vessels. A few small studies have shown some positive results but strong evidence is lacking [13-14].

Autologous blood and platelet-rich plasma injection (PRP) – In these techniques, a patient’s blood is obtained and injected whole or after processing to remove red blood cells (leaving PRP) and injected under ultrasound guidance. As with many of the treatments in this section, there are some small trials supporting its use but no high-quality studies that support it for tendinopathy.

Acupuncture – Studies of acupuncture for the treatment of tendinopathy are limited. This technique can be considered as an adjunct to exercise rehabilitation described above. Acupuncture may provide some short-term pain relief but there is no strong evidence it improves long-term outcome.

Dry needling – Like acupuncture this technique uses needles inserted through the skin. In dry needling, the practitioner attempts to cause a muscle contraction to reduce muscle spasm and tightness. Studies in the field are varied and results may be dependent on the location of the injury and the specific practitioner. More research is required, but it may be a reasonable adjunct to add if pain and function are not improving with techniques described above.

When to consider a surgical opinion for the treatment of tendinopathy

After 6 – 12 months of conservative (non-surgical) management with regular and diligent rehabilitation with adjunctive/additional techniques described above, it would be reasonable to consider surgical consultation to discuss some of the options available for the treatment of chronic tendinopathy.

Remember, rehabilitation for tendinopathy is a gradual process and can take several weeks or even months to see significant improvement. Be patient and committed to your rehabilitation plan, and don’t hesitate to reach out to your healthcare provider if you have any questions or concerns along the way. With the right treatment and care, you can successfully manage your tendinopathy and return to your normal activities.

Expert Contributor

Dr. Stephen Andrews, MD, PhD, CCFP

References

- Maffulli N, Wong J, Almekinders LC. Types and epidemiology of tendinopathy. Clin Sports Med 2003; 22:675.

- Cook JL, Malliaras P, De Luca J, et al. Neovascularization and pain in abnormal patellar tendons of active jumping athletes. Clin J Sport Med 2004; 14:296.

- Mousavizadeh R, Backman L, McCormack RG, Scott A. Dexamethasone decreases substance P expression in human tendon cells: an in vitro study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015; 54:318.

- Burnham R, Gregg R, Healy P, Steadward R. The effectiveness of topical diclofenac for lateral epicondylitis. Clin J Sport Med 1998; 8:78.

- Demirtaş RN, Oner C. The treatment of lateral epicondylitis by iontophoresis of sodium salicylate and sodium diclofenac. Clin Rehabil 1998; 12:23.

- Mazières B, Rouanet S, Guillon Y, et al. Topical ketoprofen patch in the treatment of tendinitis: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study. J Rheumatol 2005; 32:1563.

- McLauchlan GJ, Handoll HH. Interventions for treating acute and chronic Achilles tendinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001; :CD000232.

- Bisset L, Paungmali A, Vicenzino B, Beller E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials on physical interventions for lateral epicondylalgia. Br J Sports Med 2005; 39:411.

- Smidt N, van der Windt DA, Assendelft WJ, et al. Corticosteroid injections, physiotherapy, or a wait-and-see policy for lateral epicondylitis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 359:657.

- Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F. Corticosteroid injections for painful shoulder: a meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract 2005; 55:224.

- Scarpone M, Rabago DP, Zgierska A, et al. The efficacy of prolotherapy for lateral epicondylosis: a pilot study. Clin J Sport Med 2008; 18:248.

- Bertrand H, Reeves KD, Bennett CJ, et al. Dextrose Prolotherapy Versus Control Injections in Painful Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016; 97:17.

- Alfredson H, Ohberg L. Neovascularisation in chronic painful patellar tendinosis–promising results after sclerosing neovessels outside the tendon challenge the need for surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2005; 13:74.

- Alfredson H, Ohberg L. Sclerosing injections to areas of neo-vascularisation reduce pain in chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2005; 13:338.