Knee Osteoarthritis: Tips for Managing & Maintaining an Active Lifestyle

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a major cause of musculoskeletal (MSK) pain that affects more than 10% of Canadians over the age of 15 [1, 2].

It is a degenerative disease of the whole joint, including the cartilage and underlying bone, ligaments, and the capsule surrounding the joints.

The cartilage, or protective layer on the ends of your bones, breaks down leading to significant pain and loss of function.

While OA is most commonly found in the hips, knees, spine, hands, and big toes, this article will focus on OA of the knee.

Who develops OA and what does it look like?

Current research supports the theory that OA develops through a combination of traumatic injury, changes in the mechanical function and alignment of the bones, and chronic inflammation [4,5].

Individuals who have experienced a previous joint injury, such as an anterior cruciate ligament injury, or who are older, or are overweight, are at increased risk of developing OA.

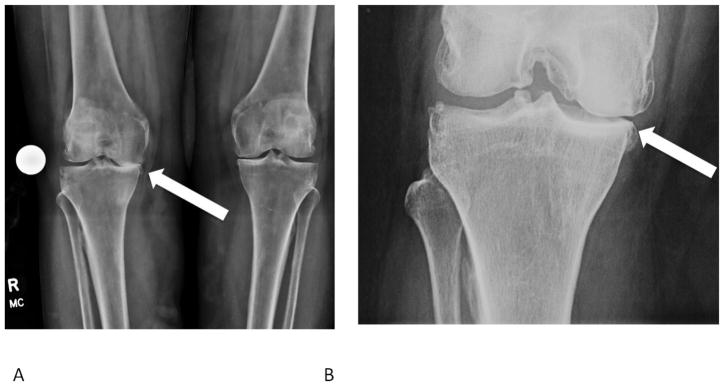

Typical symptoms include pain in the affected joint, stiffness in the joint the morning, loss of joint range of motion, and swelling. As OA progresses there are other changes that can be seen on x-ray such as loss of space between the femur and tibia, thickening of the bone surface, formation of cystic (fluid-filled) lesions, and bone spurs, as shown in the image below [6].

How is OA diagnosed?

OA can be diagnosed by your doctor based on your description of your symptoms, along with a physical examination of your affected knee.

To assess your knee function, your doctor will observe you stand and walk, assess the range of motion in the knee, and perform specific physical examination tests to check ligament function.

Sometimes your doctor will order an x-ray to better understand the extent of cartilage loss in the joint. However, there is not always a direct relationship between the severity of your symptoms and the results of the x-ray.

Therefore, it is important that you and your doctor discuss a treatment plan that is based on your symptoms and level of function.

Unfortunately, there is currently no cure for OA, but there are measures that you can take to reduce joint pain and increase your quality of life.

How can I manage OA?

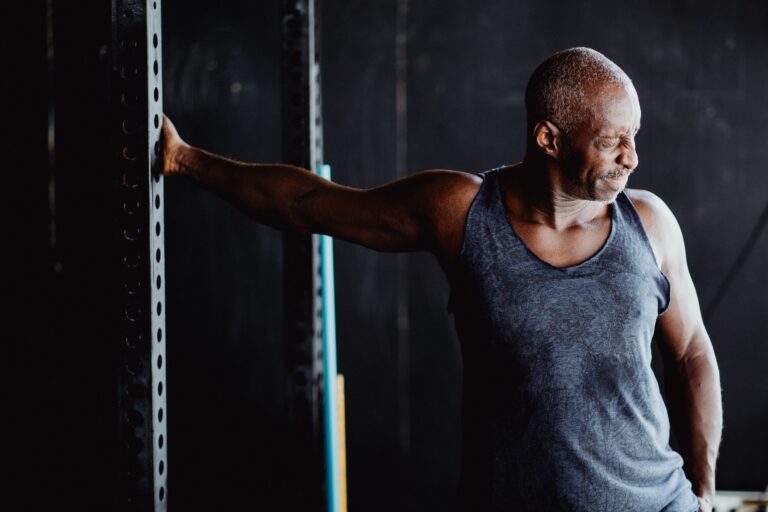

Staying Active

The first step in OA management is staying active!

Regular activity will improve pain, decrease joint stiffness, and improve overall function [7, 8].

There is no specific exercise routine that has been proven to be most effective, but studies have shown that it is important to participate in an activity that you enjoy, are motivated to do regularly, and have easy access to [9].

Anticipate experiencing some pain and swelling in your joint following exercise; this does not mean that you are damaging the joint further [10].

You may need to adjust your routine to account for recovery time between more aggressive activities. If you are experiencing joint pain the day after activity, you may have done too much the day before and could consider lowering the intensity or duration of exercise next time.

Staying active is key to managing a chronic disease like OA and will allow you to take control of your day-to-day function [9].

Weight Loss

Weight loss is often recommended as a treatment for knee OA.

This is because studies have shown that individuals with a higher body mass index (BMI) experience larger forces in their joints [11]. As a result, they develop more severe OA, decreased mobility, and higher rates of joint replacement [12, 13].

Research has shown that patients with OA who lose 10-20% of their body weight can have dramatically improved pain, function, and quality of life [14].

For this reason, if your doctor recommends weight loss, a good starting goal is 5% of your body weight.

We understand that trying to lose weight while your knee is painful and swollen can be difficult. A dietician referral may be a helpful first step.

Physiotherapy

Another effective management strategy for knee OA is physiotherapy.

Research has demonstrated that physiotherapy can improve proprioception (sensing where your joint is in space), agility, and balance [15].

Targeted exercises can also help to strengthen the muscles surrounding the knee joint, in addition to your core, hip and ankle joints, to improve joint mechanics and function [16].

Doing aquatic physiotherapy or pool-based exercises has also been shown to be very effective for improving strength and function [9].

Bracing

Bracing the affected knee is another option you may consider so that you can continue to lead an active lifestyle [9].

A common type of brace used for OA is an unloader or offloader brace which helps to reduce load on the cartilage-worn side of the joint, which re-establishes joint space.

It takes some time to get used to wearing these braces so you may need to slowly build up the time you spend wearing the brace over a few weeks.

These braces are best fitted by a qualified orthotist and your doctor can give you a referral if your knee is likely to benefit from this type of brace.

Medications

Depending on the severity of your symptoms, you may consider medication therapy in conjunction with the treatments discussed above.

Topical anti-inflammatory gels such as diclofenac can be applied to the painful joint as needed and are a good first option before starting oral medication [17].

If topical pain relievers are not effective, you can progress to oral medications such as acetaminophen (Tylenol) or NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs).

Acetaminophen is considered first line treatment for OA pain as it has no drug interactions or common contraindications [9, 16, 19]. Acetaminophen reduces pain while NSAIDs reduce both pain and swelling.

However, regular NSAID use can lead to increased risk of gastrointestinal issues such as ulcers and irritation of the stomach and intestines. For these reasons it is important to carefully review the safest way to take your medications with your doctor and pharmacist.

Prescription narcotics or opioid medications such as morphine or hydromorphone are not recommended for OA [18].

There are many supplements which claim to be beneficial for OA, however, none of these have strong evidence to demonstrate that they are safe and effective.

Before initiating any medication or supplement, you should discuss these treatments with your doctor and/or pharmacist as they can interact with other medications and cause side-effects.

Joint Injections

Another type of treatment for the symptoms of knee OA is joint injections [19, 20].

While there are many types of joint injections, three that are commonly used are cortisone, hyaluronic acid, and platelet-rich-plasma (PRP).

Cortisone is a steroid hormone and can be injected into the knee to decrease inflammation and provide short term, moderate pain relief [22].

Hyaluronic acid is a sugar molecule found naturally in cartilage that primarily helps to lubricate the joint. Hyaluronic injections have been shown to be beneficial for pain relief in the intermediate term and can improve knee function [23].

PRP injections involve taking platelets from your own blood and injecting them into the affected joint to accelerate healing. Recent evidence has demonstrated that PRP injection “has the potential to provide improvements in pain and functional outcomes up to one year after the injection in patients with mild to moderate knee OA” [24].

Injections can be a very effective tool in managing pain, keeping you active, and delaying the need for surgery.

Read more about Injections for Knee Osteoarthritis

Read more about the injections used at the Banff Sport Medicine Clinic

Surgery

In severe cases of OA, where non-surgical treatment options have failed, it may be time to consider a consultation with an orthopedic surgeon.

In patients where OA affects one side of the knee more than the other, a high tibial osteotomy (HTO) can be performed.

HTO is a procedure which off-loads the side of the knee with OA to help preserve the remaining cartilage [25]. It is a good option for improving pain and increasing function in patients who are active and reasonably fit.

A partial knee replacement may also be done for patients with lower demands on their knees, and who have intact knee ligaments, healthy cartilage in the other compartment, and sufficient knee range of motion [26].

However, if OA affects the entire knee joint, and there is significant loss of function in addition to pain, a total joint replacement should be considered.

Recovery time for each of these surgeries varies, but you should anticipate recovery taking 9-12 months before you are able to do most activities again. Your surgeon will discuss the options available with you, including the risks and benefits of each procedure, during your initial consultation.

Additional Resources

OA Research Society International guidelines for the non-surgical treatment of knee OA

Contributing Expert

Brodie Ritchie, MSc, MD Candidate, University of Alberta

References

[1] Public Health Agency of Canada. Life with Arthritis in Canada: A Personal and Public Health Challenge. 2011. Available at: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cd-mc/arthritis-arthrite/lwaic-vaaac-10/index-eng.php. Accessed: May 31, 2012.

[2] Bombardier et al. The Impact of Arthritis in Canada: Today and Over 30 Years. Arthritis Alliance of Canada, 2011. Available at: http://www.arthritisalliance.ca/images/PDF/eng/Initiatives/20111022_2200_impact_of_arthritis.pdf. Accessed: April 10, 2012.

[3] https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases–conditions/arthritis-of-the-knee/

[4] Sokolove J, Lepus CM. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: latest findings and interpretations. Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease. April 2013:77-94. doi:10.1177/1759720X12467868

[5] Eckstein et al. Five-year followup of knee joint cartilage thickness changes after acute rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Jan;67(1):152-61. doi: 10.1002/art.38881.

[6] Braun et al. “Diagnosis of osteoarthritis: imaging.” Bone vol. 51,2 (2012): 278-88. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2011.11.019

[7] Fransen & McConnell. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD004376.

[8] van Baar et al. Effectiveness of exercise in patients with osteoarthritis of hip or knee: nine months’ follow up. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(12):1123–1130.

[9] Kolasinski et al. (2020), 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee. Arthritis Rheumatol, 72: 220-233. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41142

[10] https://bsmfoundation.ca/hey-doc-will-running-wear-out-my-knees/

[11] Messier et al (2005) Weight loss reduces knee‐joint loads in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 52: 2026-2032. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.21139

[12] Bliddal et al. “Osteoarthritis, obesity and weight loss: evidence, hypotheses and horizons – a scoping review.” Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity vol. 15,7 (2014): 578-86. doi:10.1111/obr.12173

[13] Wendelboe et al. “Relationships between body mass indices and surgical replacements of knee and hip joints.” American journal of preventive medicine vol. 25,4 (2003): 290-5. doi:10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00218-6

[14] Messier et al. “Intentional Weight Loss in Overweight and Obese Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis: Is More Better?.” Arthritis care & research vol. 70,11 (2018): 1569-1575. doi:10.1002/acr.23608

[15] Smith et al. “The effectiveness of proprioceptive-based exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Rheumatology international vol. 32,11 (2012): 3339-51. doi:10.1007/s00296-012-2480-7

[16] Pendleton et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT) Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2000;59:936-944.

[17] Bariguian et al. “Topical Diclofenac, an Efficacious Treatment for Osteoarthritis: A Narrative Review.” Rheumatology and therapy vol. 7,2 (2020): 217-236. doi:10.1007/s40744-020-00196-6

[18] Bannuru et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis, Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, Volume 27, Issue 11, 2019, Pages 1578-1589 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011.

[19] https://bsmfoundation.ca/injections-knee-osteoarthritis/

[20] https://banffsportmed.ca/resources-sm/#injections

[21] Towheed et al. Acetaminophen for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD004257.

[22] Arroll & Goodyear-Smith. Corticosteroid injections for osteoarthritis of the knee: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2004; 328(7444):869.

[23] Bellamy et al. Viscosupplementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD005321.

[24] Kopka et al. “Arthroscopy Association of Canada Position Statement on Intra-Articular Injections for Knee Osteoarthritis.” Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, July 2019, doi:10.1177/2325967119860110.

[25] https://banffsportmed.ca/your-injury-knee/#hto

[26] Cao et al. “Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty vs High Tibial Osteotomy for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The Journal of arthroplasty vol. 33,3 (2018)