What happens when my ACL reconstruction fails?

The Basics of Revision ACL Reconstruction

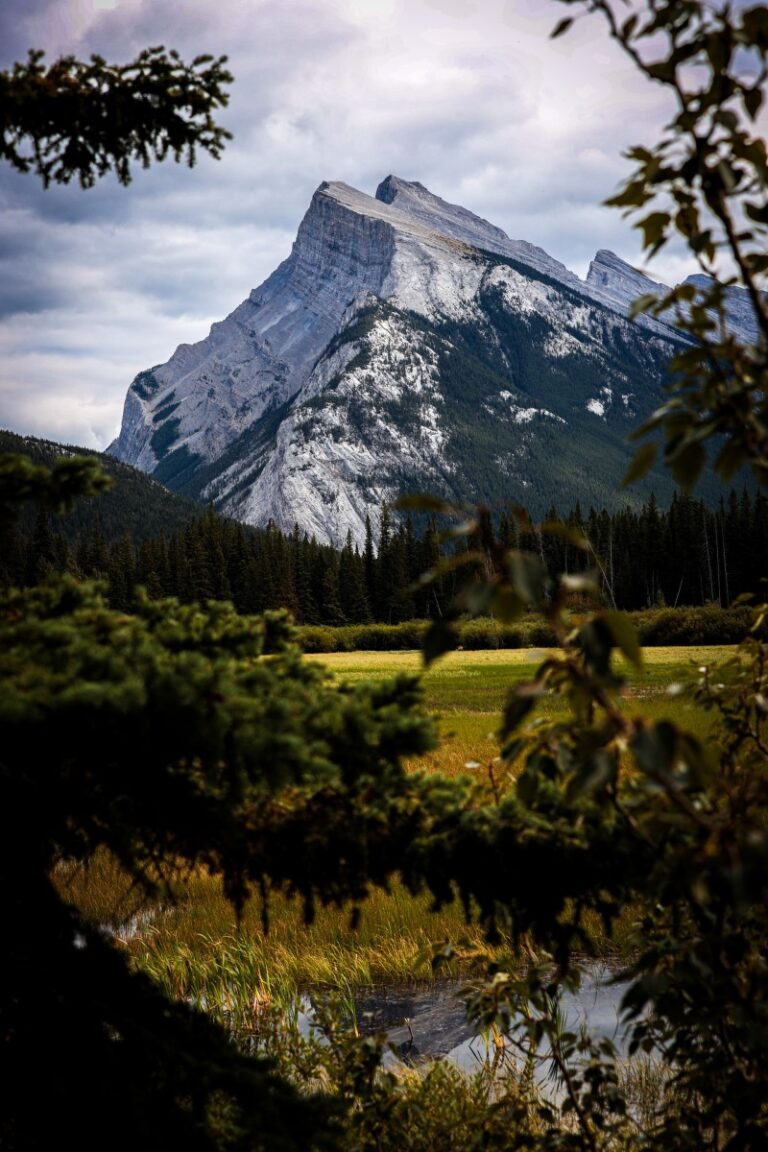

Each year, the orthopaedic surgeons at Banff Sport Medicine carry out approximately 600 Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) reconstructions due to torn ACLs.

The ACL is the main stabilizing ligament in the knee and it’s also the most commonly injured, especially in patients that participate in pivoting and cutting sports and activities such as skiing, soccer, and basketball.

— Learn more about the basics of ACL injury —

When the ACL tears, it is typically reconstructed using a donor graft in what is known as a ‘primary ACL reconstruction’. Unfortunately, just like the original ACL, the donor graft can also fail and re-tear. When this happens, the ACL can be reconstructed again in a ‘revision’ surgery.

It is estimated that approximately 5% – 10% of primary ACL reconstructions fail.

While the risk of failure is low, a revision ACL reconstruction is technically more challenging than the first, with a higher rate of failure, and lower patient satisfaction.

Why did my ACL reconstruction fail?

There are many factors that can lead to an increased risk of the primary ACL reconstruction failing or the graft re-tearing.

Acute trauma such as a blow to the knee, jumping, cutting, or changing direction are common ways to reinjure the ACL graft. Returning to sport before being fully cleared is also a risk factor, as is returning to pivoting, jumping or contact sports. Patients younger than 20 years old are also at higher risk for re-injury.

Sometimes, additional injuries to the knee structures or bony misalignments may go undiagnosed at the time of the initial surgery. These can lead to more force being placed on the graft, leading to its eventual rupture.

Missed injuries include injury to the meniscus, or to the posterolateral or posteromedial structures, while unrecognized bony alignment can include the lower limb alignment being in varus (bow legged) or having an increased posterior tibial slope.

While some of the risk factors can’t be modified (like age), having a discussion with your surgeon to understand the risk factors that are unique to you is an important part of reducing your individual risk and optimizing your post-surgical outcomes.

What does revision ACL reconstruction involve?

Evaluation before Surgery

Your surgeon will take a thorough history to understand your situation. Previous surgical notes and reports will be reviewed to understand what was done at the initial surgery and what surgical techniques and graft type were used.

A complete physical examination and diagnostic imaging (X-ray, MRI, CT) will also be done to assess for additional injuries, leg alignment, and how the original graft was positioned.

A discussion regarding goals and expectations of functional abilities will be done to match the patient’s expectation with the outcomes of a revision procedure.

Finally, the surgeon will determine the reason for the primary ACL reconstruction failure to ensure a successful revision procedure.

Single stage vs Two stage procedures

The revision ACL reconstruction can be done as either one or two surgeries.

One of the most important determining factors for this is often the location of the previous bone tunnels used to position and anchor the graft during the primary surgery.

If the old tunnels affect the placement of the new tunnels or if the tunnels have gotten bigger over time, then a two-stage procedure is typically carried out.

In a two-stage procedure, the first stage involves filling the original tunnels with a bone graft and waiting for them to heal (usually 3 – 6 months). Then, during the second surgery, new tunnels can be made to position and anchor the graft.

What type of graft can be used?

There are four types of graft that can be used for an ACL reconstruction:

- Hamstring autograft

- Bone-patella-bone autograft

- Quadricep tendon autograft

- Allograft (Achilles, tibialis anterior, tibialis posterior)

Each type of graft has advantages and disadvantages.

— Learn about the different graft types —

The difference in a revision setting is that at least one of those options has already been used in the primary surgery.

In general, an autograft is the preferred option in younger patients, while an allograft is preferred in older and less active patients.

Additional procedures

Additional surgical procedures may be done at the same time as the revision ACL reconstruction if the patient is found to have a lower limb malalignment or high posterior tibial slope. In these cases, an osteotomy is recommended.

In addition, a lateral extra-articular tenodesis, or LET, is often carried out. An LET is a surgery that uses a small slip of tissue from the iliotibial band (ITB) on the outside of the knee to add extra stability for knee rotation. Carrying out this small procedure at the same time as the revision ACL reconstruction has been found to help protect the new graft and reduce the risk of it failing again.

Does the rehabilitation differ from the first surgery?

Patients undergoing isolated revision ACL reconstruction can typically weight bear as tolerated immediately after surgery, similarly to a standard protocol after primary ACL reconstruction.

If a meniscal repair or additional osteotomy is performed during the revision surgery, weight bearing will be limited at the discretion of the surgeon to allow healing.

The rehabilitation timeline is similar if not a little longer than primary ACL reconstruction, with an expected return to sport within 1- 2 years with extensive physiotherapy.

What are the outcomes of revision ACL reconstruction?

Generally, outcomes after revision ACL reconstruction are not as good as primary ACL reconstruction. Patients are half as likely to describe their knee function as ‘’ normal’’ following revision ACL reconstruction and they return to their usual sport less often.

Thus, having a discussion with your physician regarding the goals of surgery and expectation is of paramount importance.

References

Alm L, Drenck TC, Frosch KH, Akoto R. Lateral extra-articular tenodesis in patients with revision anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction and high-grade anterior knee instability. Knee. 2020 Oct;27(5):1451-1457. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2020.06.005. Epub 2020 Aug 22. PMID: 33010761.

Bach BR. Revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(10):14-29.

Faunø P, Rahr-Wagner L, Lind M. Risk for revision after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is higher among adolescents: results from the Danish registry of knee ligament reconstruction. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine. 2014;2(10):2325967114552405.

Grassi A, Nitri M, Moulton S, Muccioli GM, Bondi A, Romagnoli M, et al. Does the type of graft affect the outcome of revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction?: a meta-analysis of 32 studies. The bone & joint journal. 2017;99(6):714-23.

Group M. Descriptive epidemiology of the Multicenter ACL Revision Study (MARS) cohort. The American journal of sports medicine. 2010;38(10):1979-86.

Kamath GV, Redfern JC, Greis PE, Burks RT. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The American journal of sports medicine. 2011;39(1):199-217.

Keene GC, Bickerstaff D, Rae PJ, Paterson RS. The natural history of meniscal tears in anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency. The American journal of sports medicine. 1993;21(5):672-9.

Lefevre N, Klouche S, Mirouse G, Herman S, Gerometta A, Bohu Y. Return to sport after primary and revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective comparative study of 552 patients from the FAST cohort. The American journal of sports medicine. 2017;45(1):34-41.

Miller MD, Kew ME, Quinn CA. Anterior cruciate ligament revision reconstruction. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2021;29(17):723-31.

Mohan R, Webster KE, Johnson NR, Stuart MJ, Hewett TE, Krych AJ. Clinical outcomes in revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a meta-analysis. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2018;34(1):289-300.

Rossi R, Bonasia DE, Amendola A. The role of high tibial osteotomy in the varus knee. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2011;19(10):590-9.

Salmon LJ, Heath E, Akrawi H, Roe JP, Linklater J, Pinczewski LA. 20-year outcomes of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring tendon autograft: the catastrophic effect of age and posterior tibial slope. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018;46(3):531-43.

Wright RW, Dunn WR, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Bergfeld J, Kaeding CC, et al. Risk of tearing the intact anterior cruciate ligament in the contralateral knee and rupturing the anterior cruciate ligament graft during the first 2 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective MOON cohort study. The American journal of sports medicine. 2007;35(7):1131-4.

Zhao D, Pan J, Lin F, et al. Risk Factors for Revision or Rerupture After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2023;51(11):3053-3075. doi:10.1177/03635465221119787