Protecting the brain: Tua Tagovailoa, concussions and the NFL

In his latest Bow Valley Crag & Canyon article, Dr. Andy Reed, discusses some misconceptions about concussions and the recent Tagovailoa incident.

It’s football season. A violent, impactful, tough and entertaining sport, but not without its dangers.

If like me, you’re an avid CFL or NFL fan, then you are well aware of the injuries, occasionally gruesome, that seem to crop up in highlight reels most weeks. Fractures, dislocations and distorted limbs seem to feature highly, but in recent weeks, the perhaps less dramatic, but no less serious, issue of concussions has come to the fore again.

For those who don’t follow pro football, there has been a huge controversy regarding the management of a head injury sustained by Miami Dolphins’ quarterback Tua Tagovailoa. During a game in week 3 of the season, Tagovailoa, the Dolphins’ star quarterback was pushed to the turf where the back of his helmet hit the turf. It looked like a fairly innocuous hit but when he stood up he was visibly dazed, and staggered twice, almost falling, before his team mates grabbed him and he left the field. NFL protocols demand that an independent neurologist assesses the player for suspected concussion, and will remove him from the game if there is any doubt. I assume that the neurologist will review the hit, talk to the player, assess their symptoms and presumably perform some rudimental physical examination designed to detect any neurological problems. I think it is fairly clear to anyone that has seen the video, that there had been an impact to the head and that Tagovailoa was demonstrating what we’d call gross motor instability – he was off-balance.

Apparently an assessment was performed and much to everyone’s surprise, he was allowed to return to the game where he played well, with the Dolphins going on to beat the favourite Buffalo Bills, in the prime time game. The skeptic in me wonders whether the fact that he was having one heck of a game, against an apparently much better opponent, had anything to do with his return, though the ‘independent’ neurology assessment is supposed to stop this from happening. In any case, there followed a lot of conjecture and debate as to how the protocol may have failed Tagovailoa. A few days later it came out that the independent NFL neurologist had been fired as several mistakes had been made during the assessment. Commentators discussed the issue at length, especially what would happen if he took another hit to the head – the so called ‘second hit’ syndrome, where an already concussed brain is subject to another hard impact, resulting in rapid brain tissue swelling with rapid neurological decline, with perhaps permanent or even fatal consequences.

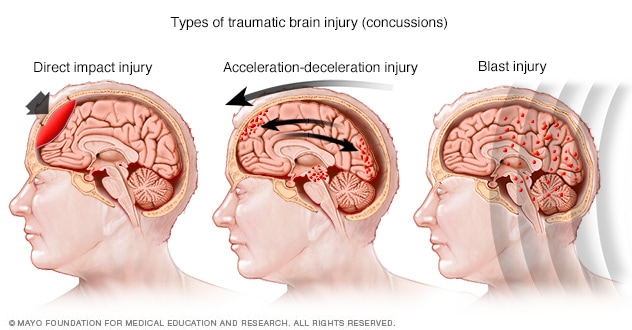

Fast forward to week 4, a mere 4 days after the first hit, where Tagovailoa took to the field against the Cincinnati Bengals during a second prime time game. The unthinkable happened. He was thrown forcefully to the ground in a tackle, hitting his head hard on the turf. This time he did not get up, but his hands contorted awkwardly in front of his face, in what is known as the Asymmetric Tonic Neck Reflex, or the fencing response. This is indicative of significant brain injury, as the cerebral cortex (our higher functioning grey matter) temporarily shuts down, and a primitive brain reflex, the fencing response, takes over. Tagovailoa was taken from the field by stretcher with full spinal precautions, as is advised, and did not return to the game. He has apparently worked through NFL concussion protocols, resumed practice, and will be returning to the field week 7, three weeks after the second hit.

Misconceptions surrounding concussion

A lot of criticism has been levelled at the team and the NFL in general over their handling of this injury, and the apparent lack of regard for the player’s health and safety. In the wake of this, apparently the protocols have been modified, but in listening to some of the commentary, it’s clear that there are still some misconceptions surrounding concussions. I’ll highlight a few of the things I have read or heard, and offer my thoughts.

Firstly, I have heard it stated that this was a clear cut concussion (after the first hit), and that the physical examination testing would have confirmed this. This is simply not true. There is no physical examination test or line of questioning that can conclusively diagnose a concussion. In fact, in many cases, symptoms are not at all clear cut, and symptoms will develop or worsen over a few hours to days. One can only have a suspicion that a player may have sustained a sport related concussion.

You may have heard the phrase “If in doubt, sit them out”. This is absolutely the best approach. Any player suspected of having a concussion should be immediately removed from any game, and should be assessed by a competent, trained individual. Coaches, trainers and team medical personnel know this. I think it’s clear that Tua should not have been allowed to return to play against the Bills in week 3, as his symptoms were suspicious enough to assume a concussion. I’m not sure what went on in the medical tent but it seems to have been inadequate.

Secondly, I have heard some discussion of imaging. In a press conference, the Dolphins stated that Tua had undergone a scan after the second hit and that there were no signs of permanent or long lasting injury. There are a few things to unpack here. Firstly, brain scans – whether that be CT or MRI – are rarely indicated in suspected concussions. Patients often ask us about these, but the fact is that a concussion is a traumatic brain injury that causes a ‘functional’ impairment rather than a structural change. The brain does not function normally for a period of time, but there is no discernible structural damage that we can easily identify on MRI or CT.

Now there are cases when scans are needed, such as when there is progressive neurological deterioration or when symptoms are developing that may indicate bleeding or swelling in the brain, but these are the exception rather than the rule. Experienced physicians are in the best position to assess this, so an assessment by your FP, in the ER or Sport Med clinic is necessary. Secondly, there is absolutely no way that a scan, if it were undertaken, could ascertain whether there is any long lasting or permanent damage. Only time can tell, and if you have watched the 2015 movie, Concussion, you will know that CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) – the degenerative brain disease thought to be related to repeated head trauma, is a diagnosis that can only be made at autopsy.

The final point I am going to make, is with reference to the severity of the initial head trauma. The initial hit in week 3, as I stated, looked pretty innocuous. This does not appear to have significant bearing on the length of time to recovery, or as to the severity of any subsequent concussive symptoms. I have seen a career ending concussion occur in a professional skier with a seemingly very ‘minor’ whiplash type mechanism, with no impact at all to the head; and I have also seen a minor hockey player, unconscious on the ice, who developed no major subsequent symptoms and was back at practice 10 days later. It really doesn’t seem to matter in terms of prognosis for returning to sports how severe the initial blow is. Again, I think this highlights that it is important to take any potential concussion seriously, to seek immediate attention, and to do everything you can to ensure a safe return to activity.

Expert Contributor

Dr. Andy Reed, Banff Sport Medicine Physician