Phases of your Banff Sport Medicine Postoperative Rehabilitation Program after ACL Reconstruction

Rehabilitation following Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Reconstruction is an essential part of a full recovery.

The ultimate goal of this rehabilitation program is to restore functional ability and enable you to return to your sport or physical activities, with a reduced risk for additional injury.

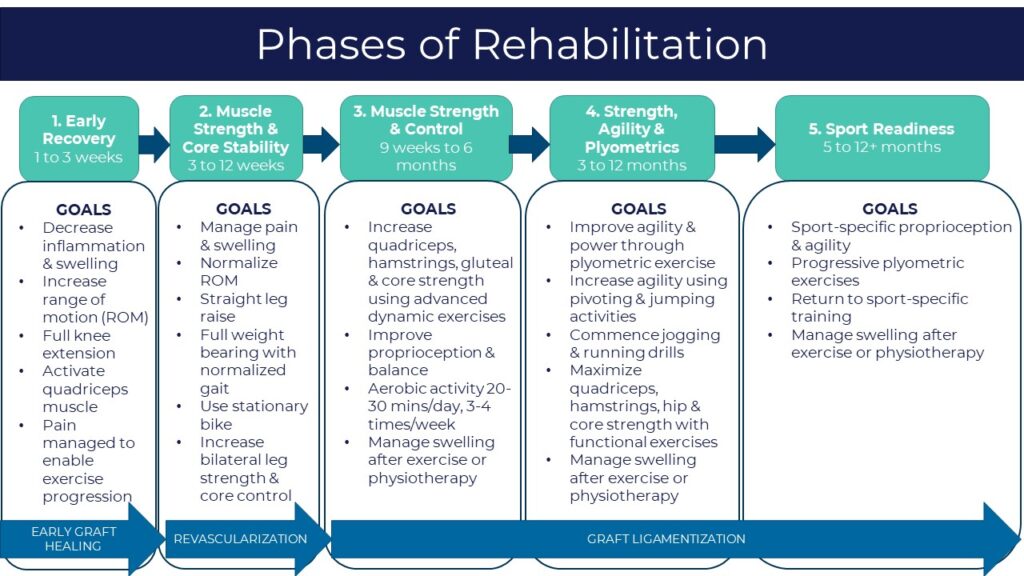

Although different surgeons and therapists will have slightly different protocols, the goals are ultimately the same. The below graphic summarizes the 5 Phases of the program recommended by your Banff Sport Medicine (BSM) Surgeon.

The timing of each phase is unique to you and will depend on several factors including what type of graft you received, the presence of secondary injury, and your commitment to complete your physical therapy exercises.

Some Phases, however, cannot begin too early due to the biological healing of the graft. For example, in the first 3 months following surgery, the graft is at its weakest and at the highest risk of injury or stretching, thus, rehabilitation activities that might lead to excessive ACL tensioning are avoided.

Biological Recovery of the ACL Graft

While rehabilitation is an essential part of a successful ACL reconstruction, so too is allowing enough time for healing of the graft into the bone tunnel and recovery of graft strength.

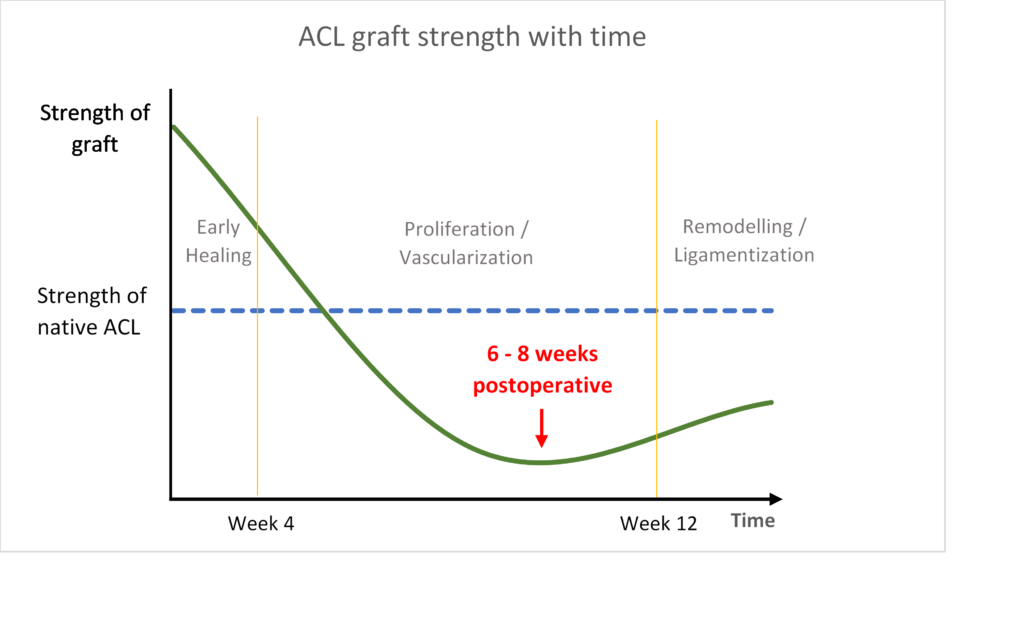

Biological recovery of the ACL graft is a gradual process that occurs over several years. The process can be divided into three distinct phases that are important to consider in the development of postoperative rehabilitation programs and timing of return to preinjury sport activities.

Animal and human studies have described the following three phases of ACL graft healing:

Phase 1: Early graft healing

This phase is defined as the period from the time of ACL reconstruction until approximately the third to fourth postoperative week. When the graft is first implanted, it is approximately twice the strength of the native ACL. During this phase, necrosis (cell death) of the tendon tissue in the graft occurs, which begins to weaken the mechanical strength of the graft.

Although the graft is still much stronger than the original ACL at this point, it still has not begun to incorporate into the bone tunnels resulting in a weak link that is greatly dependent upon the implants used for graft fixation. Graft fixation techniques have significantly improved over time, but may not prevent a few millimeters of creep, which could lead to graft laxity (looseness) at the end of the healing process if aggressive exercises are started too soon.

The remaining tissue acts like a “scaffold” for the body to begin rebuilding upon; a gradual process where ligament forming cells are later carried into the graft as it is revascularized from the surrounding tissues of the knee.

During this phase of early graft healing, rehabilitation programs focus on decreasing swelling while recovering knee extension (getting the knee straight). The earlier full knee extension is achieved, the earlier quadriceps muscle strength begins to recover. Several studies have shown that functional recovery after ACL reconstruction is directly related to quadriceps muscle strength recovery.

Phase 2: Proliferation / Revascularization

This phase is the period from the fourth postoperative week, upwards to 12 weeks. This is when revascularization of the graft occurs where blood vessels and host cells begin to migrate into the new graft tissue.

The graft continues to lose strength during this phase due to intensive remodelling. Animal studies show that the graft is at its weakest at approximately 6-8 weeks postoperative. However, human biopsy studies show that graft remodelling and revascularization is not as intense as in animals, with less disruption of the graft, although it is still logical to assume that the graft is also at its weakest in humans during this phase.

In addition, during this phase, loading of the graft must be high enough to stimulate rebuilding of the graft, but too much loading may result in laxity (elongation) or failure of the graft. While you may feel confident your knee is stable, it is important to know that the graft is still highly vulnerable to injury at this stage. Thus, rehabilitation activities during this phase avoid specific exercise and strengthening work that could stretch the graft.

Phase 3: Ligamentization

This is the final phase of graft healing where the maturing graft develops characteristics similar to the native ACL. This phase begins after the graft has healed into the bone. For example, hamstring tendon grafts heal to the bone tunnel at approximately 10-12 weeks and although the patellar tendon graft, which has bone blocks at either end, heals to the bone tunnel sooner, its tendinous intra-articular portion is still weakest at 6-8 weeks postoperative as is the case with hamstring grafts. Therefore, more aggressive rehabilitation should not be started any sooner with patellar tendon grafts.

During this phase, the graft slowly regains its strength. Collagen fibres are rebuilt and regain their organization. However, the normal architecture of the new and reorganized collagen fibres is never fully restored to that of the native ACL in terms of crimp pattern, cross-linking and collagen type (there is more type 3 collagen as is found in scar tissue, vs type 1 collagen found in normal ligaments).

Animal studies demonstrate that the structural properties (e.g. failure load, stiffness) of the healing graft do not surpass 60% of the intact ACL and that this occurs around 1 year. Similarly, the mechanical properties of the graft in humans likely do not reach the same levels of the native ACL, but the exact strength of the graft is not known as these types of strength tests are not possible in humans.

In addition, studies in humans show maturity of the graft at around 2 years after surgery. This corresponds to clinical studies, such as our own at BSM, which show that functional testing results of ACL reconstructed patients continue to improve up to 2 years postoperative.

Repetitive impact loading activities, such as running and jumping, are often introduced into the rehabilitation program during this phase as the risk of stretching the graft is relatively low.

Exceptions to rehabilitation timelines

The first is regarding allografts.

Animal studies show incorporation of allograft tendons is delayed when compared to autograft tendons.

Allograft – tendon originating from another person, typically a cadaver.

Autograft – tendon taken from another location in the patient’s body.

Although there have been no such studies to confirm this in humans, many surgeons believe that the timelines for rehabilitation programs should be somewhat delayed in these patients. For example, Phase 4 of the BSM Rehabilitation program that focuses on strength, agility and plyometrics may be safer to begin at 4 months rather than 3 months to prevent elongation of the allograft during the ligamentization phase.

Similarly, patients with generalized ligamentous laxity (loose ligaments), particularly those with excessive recurvatum (hyperextension), should be dealt with more cautiously in their rehabilitation, regardless of the type of graft used. For example, there should be no urgency in trying to achieve full knee hyperextension in the first few weeks, as long as knee extension to a neutral position can be achieved within 4-6 weeks to ensure quadriceps muscle strength recovery.

When can you return to your preinjury level of activities?

Successful ACL reconstruction depends on many factors, including how well you stick to your postoperative rehabilitation program, and the biological healing and remodelling of the graft.

Whether or not you are ready to return to your activities or sport involves several additional factors, including passing a battery of objective clinical and functional assessments (such as the ones conducted at BSM Functional Testing clinics at 6- and 12-months), your mental readiness and risk tolerance, as well as time from surgery.

The decision of when to return to your preinjury level of sport and activities will be tailored to you and will be discussed with your surgeon.

Contributing expert

Dr Greg Buchko, Orthopaedic Surgeon