Shoulder Instability 101: the basics

Shoulders are the most commonly dislocated joint[1] due to their extreme mobility.

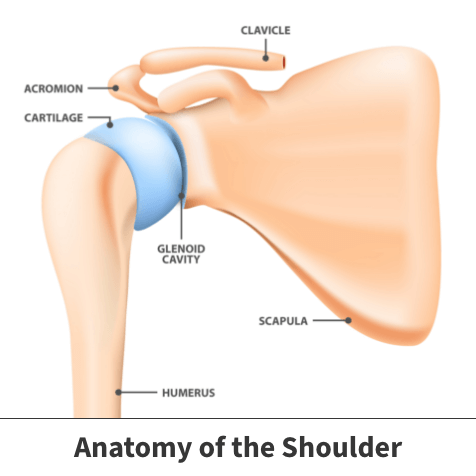

The shoulder is sometimes called a ball and socket joint. The ball of the shoulder is the rounded head of the upper arm or humerus bone, and the socket is the shallow dish on the side of the shoulder blade or scapula bone that is called the glenoid cavity.

A dislocation occurs when the ball of the humerus is moved out of its usual location in the glenoid cavity.

The majority of dislocations occur anteriorly (towards the front), due to a contact force on an outstretched arm. As the shoulder dislocates, it can cause damage to the bones of the joint and/or the labrum (cartilage), which leads to long-term instability of the shoulder and recurrent dislocations. If you experience instability in your shoulder after a dislocation, your doctor may recommend non-operative management with strengthening exercises, or an operation to tighten up the joint.

Anatomy

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the human body and has both static (stationary) and dynamic (moving) stabilizers that allow us to have motion in many different directions.

Static stabilizers are constantly providing support for the “ball-and-socket” joint, and consist of the following:

- Clavicle (collarbone)

- Humerus (arm) — “ball” of the joint

- Scapula (shoulder blade)

- Glenoid Cavity — “socket” of the joint

- Acromion

- Coracoid Process

- Ligaments — named for the two bones they connect

- Glenohumeral ligament

- Coracoclavicular ligament

- Coracohumeral ligament

- Coracoacromial ligament

- Labrum — rim of cartilage around the glenoid cavity

Dynamic stabilizers are activated to stabilize the shoulder when it is moving, and consist of the four rotator cuff muscles, the tendon of the long head of biceps, as well as other muscles that attach to the scapula.

Instability injuries

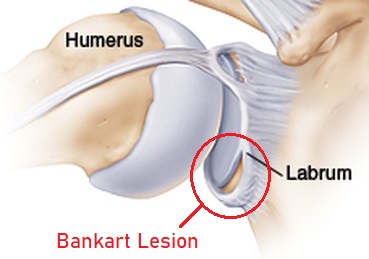

Anterior shoulder dislocations occur when a shoulder receives contact in an abducted (raised to the side) and externally rotated position (see image). This pushes the head of the humerus forward and out of the glenoid cavity. As the ball of the humerus leaves the front of the glenoid cavity, it may tear part of the labrum (cartilage), causing a Bankart lesion. If any of the underlying glenoid bone is torn away along with the labrum, it is called a bony Bankart lesion.

The ball of the humerus may also impact the glenoid cavity during the dislocation, and can suffer a small fracture on their humerus called a Hill Sachs lesion. The above injuries all contribute to the feeling of shoulder instability following repetitive dislocations.

Shoulder instability can produce many different subjective symptoms (felt by you) and objective signs (seen or felt by others)

- Subjective symptoms

- Pain in the shoulder

- Arm feels weak

- Apprehension with movement (fear that the joint might dislocate)

- Feeling like your joint is “loose”

- Objective findings

- Catching or clicking of the joint

- Muscle weakness and muscle spasms

- Subluxations — partial dislocations of the joint

- Dislocations

Management of shoulder instability

In order to diagnose shoulder instability, your doctor will perform a physical assessment which will involve putting your arm into a number of different positions[2]. Your doctor will also order some tests such as an x-ray, CT scan, or MRI to be able to see the shoulder joint and check for any injuries such as a Hill Sachs, Bankart, or bony Bankart.

If you are at low-risk for future dislocations, your doctor may recommend a trial of non-operative therapy as the first line of treatment[3]. This will include physiotherapy appointments to strengthen the dynamic stabilizers of your shoulder (your rotator cuff and other scapular muscles). Physiotherapy can improve muscle strength and coordination, and can help to reduce the mobility of the shoulder joint as well as decreasing feelings of instability. It may be necessary to modify the activities that you do in order to reduce the risk of recurrence.

For those at high-risk of future dislocations based on sport, occupation, or associated injuries, there are different surgical options to reduce instability, including the following:

- Arthroscopic or Open Bankart Repair

- Repair the injuries on the glenoid (socket) by stitching the cartilage and ligaments back in place to decrease how much the humeral head (ball) can move around

- Laterjet Procedure

- Transfer part of the coracoid process (bone from your scapula) to the glenoid to build up a strut to stop the anterior movement of the humeral head (ball)

- Glenoid Bone Graft

- Build up of the damaged glenoid (socket) with either bone from another part of the body (such as the hip) or from a donor

Recovery following surgery to stabilize a shoulder depends on the type of operation performed. In general, you will be immobilized in a sling for approximately 6 weeks, or as directed by your surgeon, and progress through phases from assisted range of motion exercises to strengthening.

Sport-specific exercises can begin around the 3-month mark post-operatively, and return to play is expected between 4-6 months for non-contact sports with a low risk of falling and 6 months for sports with contact or that have a high risk of re-injury.

Refer to the Banff Sport Medicine post-operative rehabilitation protocols for the anterior stabilization and Laterjet surgeries are linked here for additional information on post-operative recovery.

As with non-operative management, you may need to modify your activities post-operatively to reduce the risk of re-injuring the shoulder.

Expert Contributor

Halli Krzyzaniak, Doctor of Medicine Program, University of Calgary, Cumming School of Medicine

References Cited

[1] Franz S. Kralinger, et al. “Predicting Recurrence after Primary Anterior Shoulder Dislocation.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 30, no. 1, 2002, pp. 116–120.

[2] Sofu, Hakan, et al. “Recurrent Anterior Shoulder Instability: Review of the Literature and Current Concepts.” World Journal of Clinical Cases, vol. 2, no. 11, 2014, pp. 676–682.

[3] Bernard, Christopher, et al. “Anterior Shoulder Instability: Outcome of Initial Non-Operative Treatment in 739 Patients with a Mean Follow up of 15 Years.” Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 8, no. 7_suppl6, 2020, p. 2325967120.