Under Pressure: The Basics of Bone Stress Injuries

Bone stress injuries (BSI) can occur when an increased and/or repetitive stress causes weakening of the bone.

Our bodies are constantly breaking down and building new bone, which is a normal response to exercise. If the bone does not have adequate time to rest and rebuild, or is already weakened by conditions like osteoporosis, this may result in a BSI.

These types of injuries to the bone are common in sport, with some research showing BSIs account for up to 20% of all sport injuries [1,2]. They are more common in sports that involve running and jumping such as cross-country running and gymnastics [3].

BSIs can also occur in various bones of the body. For example, the most commonly affected areas in runners are the pelvis, leg bones, and bones of the feet[4].

Symptoms of Bone Stress Injuries

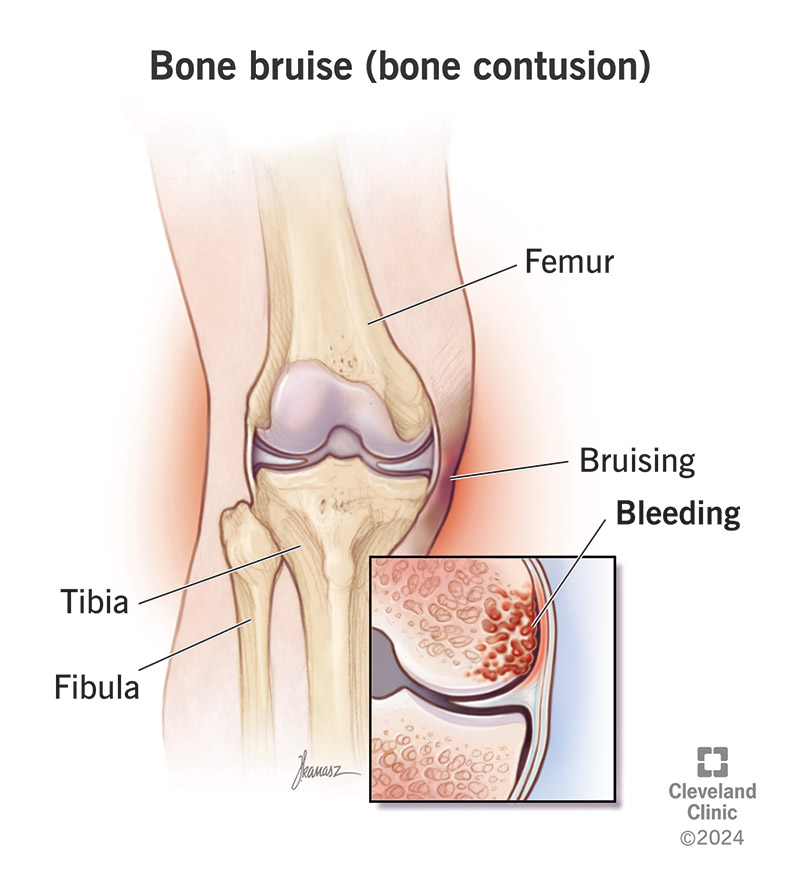

BSIs often start out with bone bruising (also known as a contusion), bone pain, and swelling. These symptoms are felt around the area of the injury and usually resolve with rest.

If the injury doesn’t heal, you may start experiencing pain with day-to-day activities like walking or going up and down stairs.

If there is further stress to the bone, this can lead to a fracture where the bone cracks and breaks.

Hence, identifying BSIs before they get worse is key!

Reach out to a healthcare provider if you are experiencing any of the following symptoms:

- A gradual onset of pain that starts and gets worse with physical activity

- BSIs are not typically associated with a pain that develops “all of a sudden” since they are an overuse injury. Physical activity aggravates the pain because it puts further stress on the existing BSI- it is your body’s way of telling you to reduce stress to the bone and allow it time to rest and recover

- A rapid increase in mileage or training load can also stress the bone with inadequate time to rebuild strong bone. This is why it’s important to gradually increase frequency or duration of physical activity, which gives our bodies time to adapt and properly remodel bone[5]

- Tenderness and swelling localized to the affected bony area

- The body responds by mounting an inflammatory response when there is microdamage to the bone, which results in pain and swelling (increased fluid)

- Pain that resolves with rest

- Rest allows the bone to recover from the microdamage it has sustained and lay down new strong bone

In the meantime, try to rest the affected area and limit stress to the bone e.g. avoid high impact physical activity such as running or jumping. Icing and/or compressing the affected area, as well as taking over-the-counter pain medications, can be beneficial for pain relief in the short term.

If you experience severe pain and/or an inability to support your own body weight, seek medical attention immediately.

Diagnosis of Bone Stress Injuries

At your doctor’s visit, they will likely assess the affected area for tenderness and swelling. They may also perform several physical exam tests to rule out other injuries.

Sometimes imaging is not necessary, and a BSI can be diagnosed from history and physical exam alone. If there is some uncertainty, your doctor may send you for an X-ay to assess for a BSI. If there is a high degree of suspicion for a BSI but the X-rays are negative, your doctor may send you for further imaging such as an MRI or bone scan to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment of Bone Stress Injuries

The earlier the BSI is identified and treated, the quicker the recovery and return to pre-injury activities.

Since BSIs are often caused by overuse, the generalized approach to treatment is to give the bone time to rest and heal. A large majority of BSIs are managed with the following conservative measures:

- Short term pain control with ice and/or pain medications such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs

- Splints or braces to protect and stabilize the affected area

- Physiotherapy to optimize biomechanics and strengthen neighboring structures

- Address modifiable risk factors (discussed below)

BSIs deemed high risk for complications of bone healing (e.g. areas with low blood flow and high mechanical stress loads) warrant evaluation by an expert such as an orthopedic surgeon or sport medicine specialist. In some cases, surgery may be needed to ensure proper healing and prevent long-term complications [6].

Risk Factors & Prevention

There are certain characteristics, or risk factors, that may mean you are at higher risk for developing a BSI. These risk factors are categorized into non-modifiable risk factors, things that you cannot change, and modifiable risk factors, things that you can change with injury prevention strategies. Non-modifiable risk factors include female sex, increased age, medical conditions causing weak bone (eg. osteoporosis) and prior injury to the affected site. Modifiable risk factors include:

- Vitamin D– Without proper Vitamin D and calcium intake, our bones can become weaker and are at higher risk of fractures. We primarily get Vitamin D from sun exposure and it is necessary to absorb calcium which is critical to build strong bone [7]. Due to our climate in Canada, we are more likely to be Vitamin D deficient and thus require supplementation.

- RED-S- Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) occurs when energy expenditure exceeds energy intake. The relative nutrient deficiency prevents proper bone remodeling, increasing the risk for BSI. Furthermore, RED-S is often associated with menstrual irregularities in females which can signify abnormalities in estrogen levels, a hormone that is important in bone formation [8]. You can read more about RED-S here.

- Physical Fitness– General physical fitness and muscle strength has been shown to be a protective factor against stress fractures [9]. It is thought that weaker muscles allow more mechanical load to be transmitted through joints in actions like running or jumping. By increasing muscle strength, you can reduce the mechanical stress to the bones and consequently, risk of BSI.

BSIs are a common sport injury that can often be treated with conservative measures of rest, ice and pain medications.

Recovery varies based on the severity of the injury, site affected and how early treatment is initiated. Current studies show that most BSIs resolve within 6 weeks to 6 months [10].

Return to activity should progress gradually using pain as a guide. If the pain returns, activities should be modified or reduced and reach a pain free state before attempting to increase activity again. If you are unsure of how to progressively increase your activities, reach out to your doctor or physiotherapist to help you create a plan to safely return to activity.

WATCH this presentation to learn more about high-risk bone stress injuries

Contributing Expert

Annie Boyd, Medical Student, Western University

References

[1] Abbott A, Bird ML, Wild E, Brown SM, Stewart G, Mulcahey MK. Part I: epidemiology and risk factors for stress fractures in female athletes. Phys Sportsmed 2020;48:17–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913847.2019.1632158.

[2] Fredericson M, Jennings F, Beaulieu C, Matheson G. Stress fractures in athletes. Top Magn Reson Imaging 2006;17:309–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/RMR.0b013e3180421c8c.

[3] Changstrom BG, Brou L, Khodaee M, Braund C, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of stress fracture injuries among us high school athletes, 2005-2006 through 2012-2013. Am J Sports Med 2015;43:26–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546514562739.

[4] Kahanov L, Eberman L, Games K, Wasik M. Diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation of stress fractures in the lower extremity in runners. Open Access J Sport Med 2015:87. https://doi.org/10.2147/oajsm.s39512.

[5] Warden SJ, Edwards WB, Willy RW. Preventing Bone Stress Injuries in Runners with Optimal Workload. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2021;19:298–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-021-00666-y.

[6] McInnis KC, Ramey LN. High-Risk Stress Fractures: Diagnosis and Management. PM R 2016;8:S113–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.09.019.

[7] Tenforde AS, Sayres LC, Sainani KL, Fredericson M. Evaluating the relationship of calcium and vitamin D in the prevention of stress fracture injuries in the young athlete: A review of the literature. PM R 2010;2:945–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.05.006.

[8] Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, Carter S, Constantini N, Lebrun C, et al. The IOC consensus statement: Beyond the Female Athlete Triad-Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). Br J Sports Med 2014;48:491–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-093502.

[9] Hoffman JR, Chapnik L, Shamis A, Givon U, Davidson B. The effect of leg strength on the incidence of lower extremity overuse injuries during military training. Mil Med 1999;164:153–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/164.2.153.

[10] Hoenig T, Eissele J, Strahl A, Popp KL, Stürznickel J, Ackerman KE, et al. Return to sport following low-risk and high-risk bone stress injuries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2023;57:427–32. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2022-106328.