“Houston, We Have a Quad Problem”: Tackling Arthrogenic Muscle Inhibition (AMI) After Knee Injury or Surgery

If you’ve ever tried to fire up your quads post-knee injury or surgery and felt like they ghosted you—welcome to the maddening world of arthrogenic muscle inhibition, or AMI. It’s the physiological equivalent of your quad saying, “Yeah nah,” and slamming the door shut just when you need it most.

What is AMI?

In simple terms, AMI is your nervous system throwing a protective tantrum.

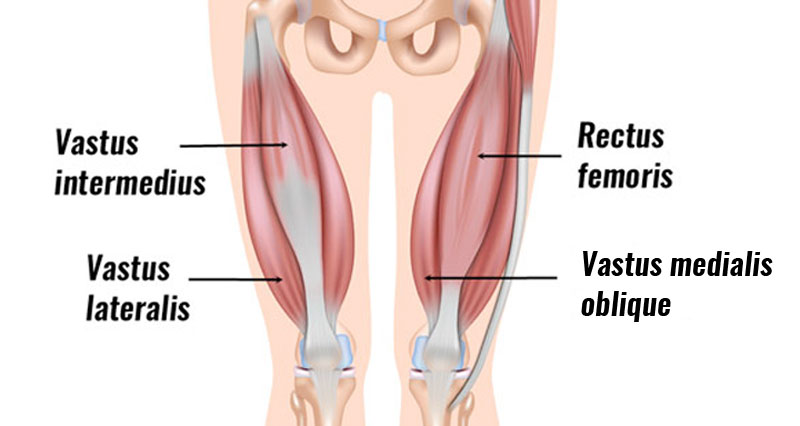

Following trauma (like an ACL tear or knee surgery), your body tries to “help” by reflexively downregulating your ability to contract certain muscles – especially your quads vastus medialis oblique (VMO) muscle, which contributes to knee stability and extension, and helps control the position of the patellar (kneecap).

The end result?

A knee extension deficit (inability to straighten the leg fully), problems with patellar tracking, and a loss of quad strength.

It’s not just about weak muscles – AMI is a central nervous system issue. We’re talking reflexes at the spinal level and even changes in how the brain processes movement. Imagine your quad being stuck in airplane mode.

While the VMO is the most affected by AMI, other muscle groups can also experience changes. The hamstrings, which act as a secondary stabilizer of the knee, often start to over-contract in response to quad inhibition.

How is AMI Graded & Why Should We Care?

AMI is more common than people think.

A recent study found that almost 60% of people post-ACL injury showed some signs of AMI.

How is it graded?

- Grade 0: Normal VMO activation and knee extension.

- Grade 1a: VMO isn’t firing properly, but function can return with basic exercises.

- Grade 1b: VMO activation needs more targeted and longer-term rehab to improve.

- Grade 2a: VMO is inhibited and there’s some knee extension loss due to tight hamstrings – both reversible with simple exercises.

- Grade 2b: Similar to 2a, but doesn’t respond to basic exercises – needs longer, more specific rehab.

- Grade 3: Chronic loss of knee extension that won’t improve without surgical intervention.

AMI can persist for months, and even years, after a knee injury or surgery, requiring a long-term approach to rehabilitation.

Left unchecked, AMI leads to:

- Loss of knee extension (which makes things like walking and climbing stairs difficult)

- Persistent knee pain

- Altered gait (walking) mechanics

- Muscle strength differences

- An increased risk of reinjury

- Delayed rehabilitation and return to sport and activity

Who’s At Risk?

Risk factors for developing AMI include:

- Knee effusion (swelling)

- High levels of pain

- Concomitant injuries (more than one injury)

To some degree, everyone experiences AMI after knee injury or surgery, however, the severity and duration vary widely.

If inhibition persists beyond 3 – 4 weeks even as swelling and pain improve, tell your physiotherapist or surgeon.

A Simple Way to Assess for AMI

To check your VMO is contracting, sit with your legs out in front and a rolled-up towel under your injured knee.

Put your fingers over the area of the VMO muscle on the inside of your thigh and contract your quads by pushing down into the towel. If the muscles are contracting properly, your knee should push down into the towel and your leg should straighten so that the foot lifts.

You should also feel a strong contraction of the muscle under your fingers. Repeat this with your uninjured side for comparison!

How Do We Fix AMI?

Identifying AMI early is key to avoiding its complications and improving outcomes for patients.

Whether it’s after injury or surgery, it’s important to control pain and swelling using cryotherapy and anti-inflammatory medications. Working to regain normal range of motion, especially in leg extension, is also important. Simple exercises paired with neuromuscular electronic stimulation (NEMS) can help retrain muscle recruitment pathways to “wake up” the quad.

Some example exercises can be found HERE.

A particularly useful technique called Neuromuscular Re-education involves retraining the nervous system and muscles to work together more effectively. This technique aims to strengthen the quad muscles by fatiguing the overactive hamstrings muscles.

While lying face down, a practitioner places a downward force on the leg while the patient is trying to resist. Overtime, this fatigues the hamstring and dampens overactivity, allowing the quad muscles the chance to recruit and activate in isolation. Watch the video demonstration below!

Overall, if you or someone you know is post-knee injury and feeling like their quad’s are on permanent vacation, reach out to a healthcare professional such as a physiotherapist, kinesiologist, or exercise physiologist, that can recognize AMI and help implement treatment strategies before it becomes a bigger issue!

This article is based, in part, on a previously published article by Jake Watson, Intrepid Performance Training, and reproduced here with permission.

Contributing Experts

Jake Watson, Exercise Physiologist, Banff Sport Medicine & Intrepid Performance Training

Anna-Lee Policicchio, PGY4 Resident, University of Calgary